Supercommunicators

Book #9

March 2025

Supercommunicators by Charles Duhigg

I didn’t set out reading Supercommunicators as a design-related read. I picked it up out of personal curiosity, to see what communication ideas I could play around with to improve my day to day communication. But, as I got going in this book, I noticed a bunch of communication strategies that I have picked up through from design mentors and experiences and use frequently in my work communications. There are some remarkable communicators in the design world, pay close attention to how mentors lead the room, make people feel heard, shift the mood. I’ll point out a few ideas from the book that I think are valuable for those of us who work in the design industry.

“Explore if identities are important to this discussion” (Identities are always important in meetings and communications about design work.)

When you go to your first meeting about a project, or meet a new client team, or have been assigned to a new interdisciplinary team, one of the most useful first tasks is to figure out who these people are and what their role on the team will be. If you’re running the meeting, make that task #1. Introduce yourself and everyone on the team, along with their role on the project. Now, when you’re collecting information, discussing, trying to understand disagreements, wonder where feedback came from… you have so much more context. In most work environments there are executive decision makers, it’s super helpful to understand who that is in meetings and communications on both the design side and the client side. Once you work with people regularly, you’ll not only know their roles, but also some additional information about them — that they want to leave on time to get home to family, that they are trying to gain experience, that they are an excellent photographer, or that they hate presenting to clients — all of that data helps you to communicate and work together better. Some folks hesitate to ask about other’s roles because it seems like you’re asking superficially about seniority and pecking order, but that information is useful in how you present or respond in conversation. If you don’t understand what someone’s role is, ask them. If you wait until you’re further into the project, you’ll miss your opportunity. You can lean on project managers and experienced staff to fill in some details about others’ identities, roles, goals and preferences.

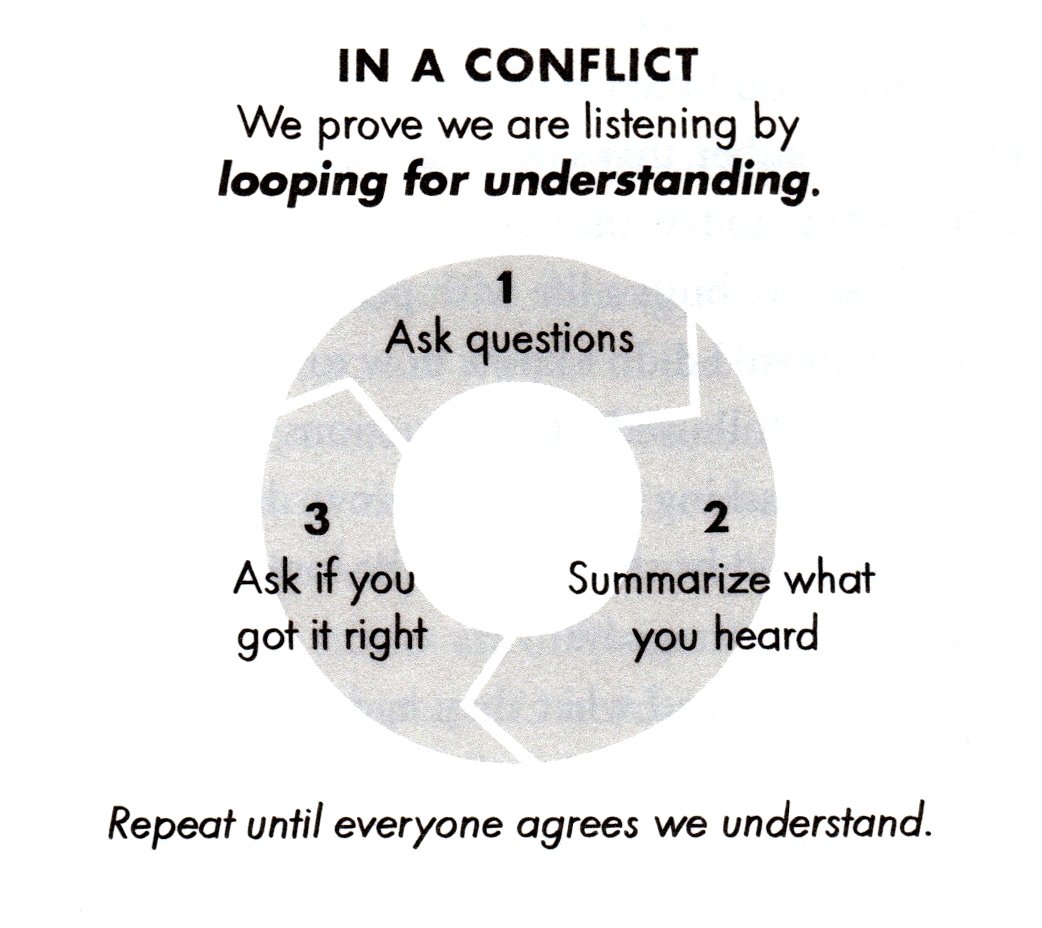

“Looping for Understanding” from Supercommunicators by Charles Duhigg.

Loop for Understanding

In the book, “Looping for Understanding” is a strategy for conflict. But, I use this approach all the time for in-real-time design feedback and never had a name for it. Usually I present layouts, give the client some time to review, comment and make decisions if they’re ready. Rarely is the feedback a list of actionable items, it’s more like a reaction and a conversation. Sometimes the client adjusts their initial instincts as they discuss. Once the client has had a chance to get through their thoughts, I usually say something like: I’m going to repeat back everything I heard, and you can tell me if I have it right — and if I don’t, you can help me get it right. I summarize everything that was said with emphasis on actionable next-steps. Often some of the feedback has really subtle contradictions, that I can clear up on the spot. You liked the color of the call out on the first layout, but you also liked how the call out on the second layout was consistent with your social media posts, which do you want to move forward with? If you don’t take the time to clarify these little things during the meeting, you can find yourself later trying to remember, guessing, attempting to clarify over email or having to make more iterations than are necessary. The most important part of this approach is that the client feels heard and understood. It’s also crystal clear what will be happening next. Sometimes when I use this on team projects, my teammates will look at me like I’m wasting everyone’s time by repeating back what everyone just heard. My experience is that it’s super reassuring to the client and you are setting yourself up for a round of revisions that are going to be spot on. If you want to win a client over, present something that they’re so-so about… listen to their feedback, get really good clarity on action items, then deliver what they asked for while upholding design quality. You can gain a lot of trust and respect in one round of revisions.

Share your goals, and ask what others are seeking

Generally, work meetings have very specific goals: gather information about an upcoming project, kick off a project, share strategy or layout. The meeting request usually has this in the title, that part is easy. If you set an expectation of what you want to have done at the end of the meeting, it helps everyone stay on task. It could be things like: I’d like to narrow this down to 2 concepts, or I would like final feedback so I can finalize the art for printing, etc. If you wait to bring this up until the end of the meeting, you might run out of time or have lost everyone’s attention. If you’re leading a meeting state an end goal “at the end of the meeting I’d like to narrow down the options to 2 preferred concepts” and if you’re a participant in the meeting, you can ask the leader “what do you want to have accomplished by the end of this meeting?” if it’s unclear.

The book advises you to watch for shifts in “What’s This Conversation Really About?”. Nearly every design meeting I’ve been in has the same formula. The first few minutes are people gathering and being polite, making sure everyone has the supplies they need to get the work done. It’s social in that everyone is trying to be welcoming, but it’s not a good time to get talking about sports or weekend plans. Then, comes the brass tacks of the meeting, where work is shared, feedback is gathered, strategy and planning is discussed. But, usually at some point when goals have been met or everyone needs a break, someone in a leadership position breaks the ice and switches the conversation to something funny or social. This shifts to a “logic of similarities” conversation where people are looking for things to talk about that aid in sharing and relating. This is the time to joke, talk about travel plans, learn about people’s dogs, hobbies, and life. If you start talking about work when everyone’s talking about going to happy hour, you’re not going to get anywhere. And if you start talking about a movie you just saw when someone’s trying to start a meeting, you’re going to irritate people. If you’re watching for those shifts to happen, you’ll notice clear divisions. Video conferences work the same way, but people don’t tend to linger socially as much at the end.

This is just a small sample of ideas from Supercommunicators and how it applies to day to day design work communications. But, the book covers a lot more: having conversations about tough topics, talking with people who don’t agree with you, how our social identities play a role in communication, and helping people to feel safe enough to have a conversation.